Creating Woodcuts Enabled Artists To

Woodcut is a relief press technique in printmaking. An artist carves an image into the surface of a block of forest—typically with gouges—leaving the printing parts level with the surface while removing the non-printing parts. Areas that the artist cuts abroad deport no ink, while characters or images at surface level carry the ink to produce the print. The block is cutting along the wood grain (dissimilar forest engraving, where the block is cut in the end-grain). The surface is covered with ink by rolling over the surface with an ink-covered roller (brayer), leaving ink upon the apartment surface just not in the non-printing areas.

Multiple colors tin be printed by keying the paper to a frame around the woodblocks (using a dissimilar block for each colour). The art of etching the woodcut can be called "xylography", but this is rarely used in English language for images alone, although that and "xylographic" are used in connection with block books, which are small books containing text and images in the same cake. They became pop in Europe during the latter one-half of the 15th century. A unmarried-canvas woodcut is a woodcut presented every bit a single epitome or impress, as opposed to a book illustration.

Since its origins in Mainland china, the practice of woodcut has spread around the globe from Europe to other parts of Asia, and to Latin America.[1]

Segmentation of labour [edit]

In both Europe and Due east Asia, traditionally the creative person just designed the woodcut, and the block-carving was left to specialist craftsmen, called formschneider or block-cutters, some of whom became well known in their own right. Amidst these, the best-known are the 16th-century Hieronymus Andreae (who also used "Formschneider" as his surname), Hans Lützelburger and Jost de Negker, all of whom ran workshops and also operated as printers and publishers. The formschneider in turn handed the block on to specialist printers. There were further specialists who made the bare blocks.

This is why woodcuts are sometimes described by museums or books as "designed by" rather than "by" an artist; but nigh authorities practise not use this distinction. The sectionalisation of labour had the advantage that a trained artist could accommodate to the medium relatively easily, without needing to learn the utilise of woodworking tools.

There were various methods of transferring the artist'due south drawn design onto the block for the cutter to follow. Either the drawing would be made directly onto the block (ofttimes whitened first), or a drawing on paper was glued to the block. Either way, the artist'southward drawing was destroyed during the cutting procedure. Other methods were used, including tracing.

In both Europe and Eastward Asia in the early 20th century, some artists began to do the whole process themselves. In Japan, this movement was called sōsaku-hanga ( 創作版画 , creative prints ), as opposed to shin-hanga ( 新版画 , new prints ), a movement that retained traditional methods. In the West, many artists used the easier technique of linocut instead.

Methods of press [edit]

The Crab that played with the sea, Woodcut by Rudyard Kipling illustrating one of his Simply So Stories (1902). In mixed white-line (beneath) and normal woodcut (above).

Compared to intaglio techniques like etching and engraving, but depression pressure is required to impress. As a relief method, it is only necessary to ink the block and bring information technology into firm and even contact with the paper or cloth to achieve an acceptable print. In Europe, a variety of wood including boxwood and several nut and fruit woods similar pear or cherry were commonly used;[two] in Nippon, the wood of the crimson species Prunus serrulata was preferred.[ citation needed ]

There are iii methods of printing to consider:

- Stamping: Used for many fabrics and near early European woodcuts (1400–40). These were printed by putting the paper/cloth on a tabular array or other apartment surface with the block on top, and pressing or hammering the back of the block.

- Rubbing: Manifestly the virtually common method for Far Eastern printing on paper at all times. Used for European woodcuts and block-books afterwards in the fifteenth century, and very widely for cloth. Also used for many Western woodcuts from nigh 1910 to the nowadays. The block goes confront up on a table, with the paper or fabric on top. The back is rubbed with a "hard pad, a flat slice of wood, a burnisher, or a leather frotton".[3] A traditional Japanese tool used for this is chosen a baren. Later on in Japan, complex wooden mechanisms were used to assistance concur the woodblock perfectly still and to employ proper pressure level in the printing process. This was especially helpful once multiple colors were introduced and had to be applied with precision atop previous ink layers.

- Printing in a printing: presses only seem to have been used in Asia in relatively recent times. Printing-presses were used from about 1480 for European prints and block-books, and earlier that for woodcut book illustrations. Simple weighted presses may have been used in Europe earlier the print-printing, but firm evidence is defective. A deceased Abbess of Mechelen in 1465 had "unum instrumentum ad imprintendum scripturas et ymagines ... cum fourteen aliis lapideis printis"—"an instrument for press texts and pictures ... with 14 stones for printing". This is probably too early to be a Gutenberg-blazon press printing in that location.[3]

History [edit]

Main articles Old main print for Europe, Woodblock printing in Nihon for Japan, and Lubok for Russia

Madonna del Fuoco (Madonna of the Burn, c. 1425), Cathedral of Forlì, in Italy

A less sophisticated woodcut book illustration of the Hortus Sanitatis lapidary, Venice, Bernardino Benaglio e Giovanni de Cereto (1511)

Woodcut originated in People's republic of china in antiquity every bit a method of printing on textiles and later on newspaper. The earliest woodblock printed fragments to survive are from Prc, from the Han dynasty (before 220), and are of silk printed with flowers in three colours.[four] "In the 13th century the Chinese technique of blockprinting was transmitted to Europe."[5] Paper arrived in Europe, also from China via al-Andalus, slightly later, and was beingness manufactured in Italian republic by the end of the thirteenth century, and in Burgundy and Frg by the end of the fourteenth.

In Europe, woodcut is the oldest technique used for old master prints, developing about 1400, by using, on newspaper, existing techniques for printing. Ane of the more ancient woodcuts on paper that tin can be seen today is The Burn Madonna (Madonna del Fuoco, in the Italian language), in the Cathedral of Forlì, in Italy.

The explosion of sales of cheap woodcuts in the center of the century led to a fall in standards, and many popular prints were very crude. The development of hatching followed on rather afterward than engraving. Michael Wolgemut was meaning in making German woodcuts more sophisticated from about 1475, and Erhard Reuwich was the first to apply cross-hatching (far harder to do than engraving or etching). Both of these produced mainly book-illustrations, as did various Italian artists who were likewise raising standards there at the same menses. At the stop of the century Albrecht Dürer brought the Western woodcut to a level that, arguably, has never been surpassed, and profoundly increased the condition of the "unmarried-leaf" woodcut (i.due east. an image sold separately).

Because woodcuts and movable type are both relief-printed, they can hands be printed together. Consequently, woodcut was the primary medium for book illustrations until the late sixteenth century. The first woodcut book illustration dates to about 1461, merely a few years after the kickoff of printing with movable type, printed by Albrecht Pfister in Bamberg. Woodcut was used less often for private ("single-leaf") fine-art prints from nigh 1550 until the late nineteenth century, when interest revived. Information technology remained important for pop prints until the nineteenth century in most of Europe, and after in some places.

The fine art reached a high level of technical and creative development in East Asia and Islamic republic of iran. Woodblock printing in Japan is called moku-hanga and was introduced in the seventeenth century for both books and art. The popular "floating world" genre of ukiyo-e originated in the second half of the seventeenth century, with prints in monochrome or two colours. Sometimes these were hand-coloured after printing. Later, prints with many colours were developed. Japanese woodcut became a major artistic grade, although at the time it was accorded a much lower condition than painting. It continued to develop through to the twentieth century.

White-line woodcut [edit]

Using a handheld gouge to cut a "white-line" woodcut blueprint into Japanese plywood. The design has been sketched in chalk on a painted face of the plywood.

This technique simply carves the prototype in by and large sparse lines, similar to a rather rough engraving. The block is printed in the normal way, so that most of the print is black with the image created by white lines. This procedure was invented by the sixteenth-century Swiss creative person Urs Graf, merely became most popular in the nineteenth and twentieth century, often in a modified grade where images used large areas of white-line contrasted with areas in the normal blackness-line style. This was pioneered by Félix Vallotton.

Japonism [edit]

In the 1860s, just as the Japanese themselves were becoming enlightened of Western fine art in general, Japanese prints began to reach Europe in considerable numbers and became very stylish, especially in France. They had a great influence on many artists, notably Édouard Manet, Pierre Bonnard, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Edgar Degas, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, Félix Vallotton and Mary Cassatt. In 1872, Jules Claretie dubbed the trend "Le Japonisme".[6]

Though the Japanese influence was reflected in many artistic media, including painting, it did pb to a revival of the woodcut in Europe, which had been in danger of extinction as a serious art medium. Most of the artists above, except for Félix Vallotton and Paul Gauguin, in fact used lithography, specially for coloured prints. Run into below for Japanese influence in illustrations for children'south books.

Artists, notably Edvard Munch and Franz Masereel, continued to use the medium, which in Modernism came to entreatment because information technology was relatively easy to complete the whole process, including printing, in a studio with little special equipment. The German language Expressionists used woodcut a good deal.

Colour [edit]

Coloured woodcuts first appeared in ancient China. The oldest known are three Buddhist images dating to the 10th century. European woodcut prints with coloured blocks were invented in Frg in 1508, and are known as chiaroscuro woodcuts (see beneath). All the same, colour did not get the norm, as it did in Japan in the ukiyo-due east and other forms.

In Europe and Japan, colour woodcuts were normally only used for prints rather than book illustrations. In China, where the individual impress did not develop until the nineteenth century, the reverse is true, and early on colour woodcuts mostly occur in luxury books most art, particularly the more prestigious medium of painting. The first known example is a book on ink-cakes printed in 1606, and colour technique reached its peak in books on painting published in the seventeenth century. Notable examples are Hu Zhengyan'south Treatise on the Paintings and Writings of the Ten Bamboo Studio of 1633,[seven] and the Mustard Seed Garden Painting Manual published in 1679 and 1701.[8]

In Japan colour technique, chosen nishiki-e in its fully developed form, spread more widely, and was used for prints, from the 1760s on. Text was nearly always monochrome, as were images in books, but the growth of the popularity of ukiyo-due east brought with information technology demand for ever-increasing numbers of colors and complexity of techniques. By the nineteenth century most artists worked in color. The stages of this evolution were:

- Sumizuri-e (墨摺り絵, "ink printed pictures") – monochrome press using only black ink

- Benizuri-e (紅摺り絵, "ruby printed pictures") – reddish ink details or highlights added by hand afterward the press procedure;dark-green was sometimes used as well

- Tan-e (丹絵) – orange highlights using a red pigment called tan

- Aizuri-due east (藍摺り絵, "indigo printed pictures"), Murasaki-due east (紫絵, "purple pictures"), and other styles that used a single color in addition to, or instead of, black ink

- Urushi-eastward (漆絵) – a method that used glue to thicken the ink, emboldening the image; gold, mica and other substances were often used to raise the paradigm further. Urushi-e can besides refer to paintings using lacquer instead of paint; lacquer was very rarely if ever used on prints.

- Nishiki-east (錦絵, "brocade pictures") – a method that used multiple blocks for separate portions of the image, and then a number of colors could achieve incredibly complex and detailed images; a separate block was carved to use only to the portion of the image designated for a single color. Registration marks called kentō (見当) ensured correspondence between the application of each block.

A number of dissimilar methods of color printing using woodcut (technically Chromoxylography) were developed in Europe in the 19th century. In 1835, George Baxter patented a method using an intaglio line plate (or occasionally a lithograph), printed in black or a dark color, so overprinted with upwards to twenty different colours from woodblocks. Edmund Evans used relief and woods throughout, with up to eleven different colours, and latterly specialized in illustrations for children's books, using fewer blocks simply overprinting non-solid areas of colour to achieve composite colours. Artists such as Randolph Caldecott, Walter Crane and Kate Greenaway were influenced by the Japanese prints now bachelor and fashionable in Europe to create a suitable style, with flat areas of color.

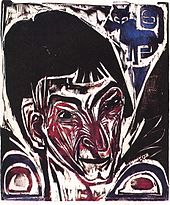

In the 20th century, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner of the Die Brücke group developed a process of producing colored woodcut prints using a single block applying different colors to the block with a castor à la poupée and then printing (halfway between a woodcut and a monotype).[ix] A remarkable example of this technique is the 1915 Portrait of Otto Müller woodcut print from the collection of the British Museum.[ten]

Gallery of Asian woodcuts [edit]

Chiaroscuro woodcuts [edit]

Chiaroscuro woodcut depicting Playing cupids by anonymous 16th-century Italian artist

Chiaroscuro woodcuts are old primary prints in woodcut using two or more blocks printed in unlike colours; they do not necessarily characteristic strong contrasts of calorie-free and dark. They were start produced to achieve like effects to chiaroscuro drawings. After some early on experiments in book-printing, the truthful chiaroscuro woodcut conceived for ii blocks was probably beginning invented by Lucas Cranach the Elderberry in Frg in 1508 or 1509, though he backdated some of his first prints and added tone blocks to some prints outset produced for monochrome printing, swiftly followed by Hans Burgkmair.[eleven] Despite Giorgio Vasari's claim for Italian precedence in Ugo da Carpi, it is clear that his, the showtime Italian examples, engagement to effectually 1516.[12] [13]

Other printmakers to use the technique include Hans Baldung and Parmigianino. In the German states the technique was in use largely during the start decades of the sixteenth century, but Italians continued to use it throughout the century, and later on artists like Hendrik Goltzius sometimes made utilize of it. In the High german way, one block ordinarily had only lines and is chosen the "line cake", whilst the other block or blocks had apartment areas of colour and are called "tone blocks". The Italians usually used only tone blocks, for a very different effect, much closer to the chiaroscuro drawings the term was originally used for, or to watercolor paintings.[14]

The Swedish printmaker Torsten Billman (1909–1989) developed during the 1930s and 1940s a variant chiaroscuro technique with several grayness tones from ordinary printing ink. The art historian Gunnar Jungmarker (1902–1983) at Stockholm'southward Nationalmuseum chosen this technique "grisaille woodcut". It is a time-consuming printing procedure, exclusively for hand printing, with several grey-wood blocks aside from the black-and-white central block.[fifteen]

Modern woodcut press in Mexico [edit]

José Guadalupe Posada, Calavera Oaxaqueña, 1910

Woodcut printmaking became a pop form of art in Mexico during the early on to mid 20th century.[1] The medium in Mexico was used to convey political unrest and was a class of political activism, especially after the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920). In Europe, Russia, and Red china, woodcut art was existence used during this fourth dimension besides to spread leftist politics such as socialism, communism, and anti-fascism.[sixteen] In Mexico, the art mode was fabricated popular by José Guadalupe Posada, who was known as the male parent of graphic art and printmaking in Mexico and is considered the first Mexican modernistic artist.[17] [eighteen] He was a satirical cartoonist and an engraver before and during the Mexican Revolution and he popularized Mexican folk and indigenous art. He created the woodcut engravings of the iconic skeleton (calaveras) figures that are prominent in Mexican arts and culture today (such as in Disney Pixar's Coco).[19] Meet La Calavera Catrina for more on Posada's calaveras.

In 1921, Jean Charlot, a French printmaker moved to Mexico City. Recognizing the importance of Posada'due south woodcut engravings, he started teaching woodcut techniques in Coyoacán's open-air art schools. Many immature Mexican artists attended these lessons including the Fernando Leal.[17] [18] [xx]

After the Mexican Revolution, the state was in political and social upheaval - there were worker strikes, protests, and marches. These events needed cheap, mass-produced visual prints to exist pasted on walls or handed out during protests.[17] Information needed to be spread quickly and cheaply to the general public.[17] Many people were notwithstanding illiterate during this time and there was push later the Revolution for widespread didactics. In 1910 when the Revolution began, only xx% of Mexican people could read.[21] Art was considered to be highly important in this cause and political artists were using journals and newspapers to communicate their ideas through illustration.[18] El Machete (1924–29) was a pop communist journal that used woodcut prints.[xviii] The woodcut fine art served well because information technology was a popular manner that many could understand.

Artists and activists created collectives such as the Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP) (1937–present) and The Treintatreintistas (1928–1930) to create prints (many of them woodcut prints) that reflected their socialist and communist values.[22] [twenty] The TGP attracted artists from all around the earth including African American printmaker Elizabeth Catlett, whose woodcut prints later influenced the art of social movements in the Us in the 1960s and 1970s.[1] The Treintatreintistas fifty-fifty taught workers and children. The tools for woodcut are easily attainable and the techniques were elementary to learn. It was considered an fine art for the people.[twenty]

Mexico at this fourth dimension was trying to notice its identity and develop itself as a unified nation. The course and style of woodcut artful allowed a various range of topics and visual civilisation to look unified. Traditional, folk images and avant-garde, modern images, shared a similar aesthetic when it was engraved into forest. An image of the countryside and a traditional farmer appeared like to the image of a city.[xx] This symbolism was beneficial for politicians who wanted a unified nation. The physical deportment of carving and printing woodcuts besides supported the values many held virtually manual labour and supporting worker'southward rights.[twenty]

Current woodcut practices in United mexican states [edit]

Today, in United mexican states the activist woodcut tradition is still alive. In Oaxaca, a commonage called the Asamblea De Artistas Revolucionarios De Oaxaca (ASARO) was formed during the 2006 Oaxaca protests. They are committed to social alter through woodcut art.[23] Their prints are fabricated into wheat-paste posters which are secretly put up around the city.[24] Artermio Rodriguez is another artist who lives in Tacambaro, Michoacán who makes politically charged woodcut prints about contemporary bug.[one]

Famous works in woodcut [edit]

Europe

- Ars moriendi

- Dürer'due south Rhinoceros

- Emblem books

- Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

- Hypnerotomachia Poliphili

- Just And then Stories

- Lubok prints

- Nuremberg Chronicle

Japan (Ukiyo-e)

- Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre

- The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife

- Xxx-six Views of Mount Fuji (includes The Great Wave off Kanagawa)

Notable artists [edit]

The Prophet, woodcut by Emil Nolde, 1912, various collections

- Irving Amen

- Mary Azarian

- Aubrey Beardsley

- Hans Baldung

- Leonard Baskin

- Gustave Baumann

- Torsten Billman

- Carroll Thayer Berry

- Emma Bormann

- Erich Buchholz

- Hans Burgkmair

- Domenico Campagnola

- Ugo da Carpi

- Baton Kittenish

- Salvador Dalí

- Gustave Doré

- Albrecht Dürer

- Thousand. C. Escher

- James Flora

- Antonio Frasconi

- Robert Gibbings

- Vincent van Gogh

- Urs Graf

- Suzuki Harunobu

- Hiroshige

- Damien Hirst

- Jacques Hnizdovsky

- Hokusai

- Tom Huck

- Stephen Huneck

- Alfred Garth Jones

- Hussein el gebaly

- Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

- Gaga Kovenchuk

- Käthe Kollwitz

- J.J. Lankes

- James Duard Marshall

- Frans Masereel

- Hishikawa Moronobu

- Edvard Munch

- Emil Nolde

- Giovanni Battista Palumba (Master I.B. with a Bird)

- Jacob Pins

- J. G. Posada

- Endi E. Poskovic

- Hannah Tompkins

- Henriette Tirman

- Clément Serveau

- Paul Signac

- Eric Slater

- Marcelo Soares

- Utamaro

- Félix Vallotton

- Karel Vik

- Leopold Wächtler

- Sylvia Solochek Walters

- Susan Dorothea White

Stonecut [edit]

In parts of the world (such as the arctic) where woods is rare and expensive, the woodcut technique is used with rock as the medium for the engraved image.[25]

Run across also [edit]

- Cake book – Early Western block-printed volume

- Chiaroscuro – Utilise of strong contrasts between light and dark in fine art

- Cordel literature – Brazilian literary genre

- Linocut – Printmaking technique

- Metalcut – Early on printmaking technique

- Old chief print – Work of fine art made printing on paper in the West

- Printmaking – Process of creating artworks by press, normally on paper

- Rubber stamp – Small tool for over-press

- Shin-hanga – "New prints": 20C Japanese art move

- Sōsaku-hanga – "Creative prints" 20C Japanese art movement

- Wood etching – Form of working woods past means of a cutting tool

- Woodblock printing – Early press technique using carved wooden blocks

- Ukiyo-east – Genre of Japanese art which flourished from the 17th through 19th centuries

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b c d "Gouge: The Modern Woodcut 1870 to Now – Hammer Museum". The Hammer Museum . Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ^ Landau & Parshall, 21–22; Uglow, 2006. p. xiii.

- ^ a b Hind, Arthur 1000. (1963). An Introduction to a History of Woodcut. Houghton Mifflin Co. 1935 (in Us), reprinted Dover Publications, 1963. pp. 64–94. ISBN978-0-486-20952-4.

- ^ Shelagh Vainker in Anne Farrer (ed), "Caves of the Thousand Buddhas", 1990, British Museum publications, ISBN 0-7141-1447-two

- ^ Hsü, Immanuel C. Y. (1970). The Rise of Modernistic China. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 830. ISBN978-0-19-501240-8.

- ^ Ives, C F (1974). The Great Wave: The Influence of Japanese Woodcuts on French Prints . The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN978-0-87099-098-4.

- ^ "Shi zhu zhai shu hua pu, or, X Bamboo Studio collection of calligraphy and painting". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved xi Baronial 2015.

- ^ Fifty Sickman & A Soper, "The Art and Architecture of China", Pelican History of Fine art, 3rd ed 1971, Penguin, LOC 70-125675

- ^ Carey, Frances; Griffiths, Antony (1984). The Print in Deutschland, 1880–1933: The Age of Expressionism. London: British Museum Printing. ISBN978-0-7141-1621-1.

- ^ "Portrait of Otto Müller (1983,0416.3)". British Museum Collection Database. London: British Museum. Retrieved 5 June 2010.

- ^ so Landau and Parshall, 179–192; but Bartrum, 179 and Renaissance Impressions: Chiaroscuro Woodcuts from the Collections of Georg Baselitz and the Albertina, Vienna, Majestic Academy, London, March–June 2014, exhibition guide, both credit Cranach with the innovation in 1507.

- ^ Landau and Parshall, 150

- ^ "Ugo da Carpi after Parmigianino: Diogenes (17.50.i) | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". Metmuseum.org. 3 Feb 2012. Retrieved xviii February 2012.

- ^ Landau and Parshall, The Renaissance Print, pp. 179–202; 273–81 & passim; Yale, 1996, ISBN 0-300-06883-2

- ^ Sjöberg, Leif, Torsten Billman and the Wood Engraver'south Fine art, pp. 165–171. The American Scandinavian Review, Vol. LXI, No. two, June 1973. New York 1973.

- ^ Hung, Chang-Tai (1997). "Two images of Socialism: Woodcuts in Chinese Communist Politics". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 39 (i): 34–sixty. JSTOR 179238.

- ^ a b c d McDonald, Marking (2016). "Printmaking in United mexican states, 1900–1950". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ a b c d Azuela, Alicia (1993). "El Machete and Frente a Frente: Fine art Committed to Social Justice in United mexican states". Fine art Periodical. 52 (i): 82–87. doi:x.2307/777306. ISSN 0004-3249. JSTOR 777306.

- ^ Wright, Melissa W. (2017). "Visualizing a state without a future: Posters for Ayotzinapa, Mexico and the struggles against country terror". Geoforum. 102: 235–241. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.ten.009. S2CID 149103719.

- ^ a b c d eastward Montgomery, Harper (Dec 2011). ""Enter for Free": Exhibiting Woodcuts on a Street Corner in Mexico City". Art Journal. seventy (4): 26–39. doi:10.1080/00043249.2011.10791070. ISSN 0004-3249. S2CID 191506425.

- ^ "Mexico: An Emerging Nation's Struggle Toward Education". Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Pedagogy. 5 (2): eight–ten. 1 September 1975. doi:x.1080/03057927509408824. ISSN 0305-7925.

- ^ Avila, Theresa (four May 2014). "El Taller de Gráfica Popular and the Chronicles of Mexican History and Nationalism". Third Text. 28 (iii): 311–321. doi:10.1080/09528822.2014.930578. ISSN 0952-8822. S2CID 145728815.

- ^ "ASARO—Asamblea de Artistas Revolucionarios de Oaxaca | Hashemite kingdom of jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art". jsma.uoregon.edu . Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ Graham De La Rosa, Michael; Gilbert, Samuel (25 March 2017). "Oaxaca's revolutionary street fine art". Al Jazeera . Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ John Feeney (1963). Eskimo Artist Kenojuak. National Film Board of Canada.

References [edit]

- Bartrum, Giulia; German language Renaissance Prints, 1490–1550; British Museum Printing, 1995, ISBN 0-7141-2604-7

- Lankes, JJ (1932). A Woodcut Manual. H. Holt.

- David Landau & Peter Parshall, The Renaissance Print, Yale, 1996, ISBN 0-300-06883-two

- Uglow, Jenny (2006). Nature's Engraver: A Life of Thomas Bewick. Faber and Faber.

External links [edit]

![]()

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Woodcuts.

- Ukiyo-e from the Metropolitan Museum of Fine art Timeline of Art History

- Woodcut in Europe from the Metropolitan Museum of Fine art Timeline of Art History

- Italian Renaissance Woodcut Book Illustration from the Metropolitan Museum of Art Timeline of Art History

- Prints & People: A Social History of Printed Pictures, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on woodcuts

- Museum of Modern Fine art information on printing techniques and examples of prints.

- Woodcut in early printed books (online exhibition from the Library of Congress)

- A collection of woodcuts images can be found at the University of Houston Digital Library Archived ane Nov 2012 at the Wayback Motorcar

- Meditations, or the Contemplations of the Most Devout is a 15th-century publication that is considered the starting time Italian illustrated volume, using early woodcut techniques.

Creating Woodcuts Enabled Artists To,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Woodcut

Posted by: mathewsfusent.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Creating Woodcuts Enabled Artists To"

Post a Comment